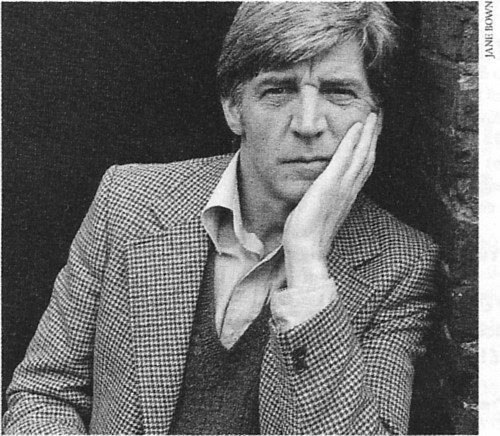

The anger, the passionate intensity and the singular vision of Bill Douglas are remembered here by Mamoun Hassan, who worked with the director on the Trilogy films.

The happiest I have ever known Bill Douglas was on our first day at the 1972 Venice Film Festival. Our rooms at the Hôtel des Bains on the Lido, the setting for Death in Venice, had been given away and we were re-booked into a hotel in Venice itself. A beautiful white launch crewed by two matelots in striped shirts sped us across the bay towards that magical skyline of Canaletto and Turner. Bill, his hair streaming in the breeze, laughed and laughed: “If only they could see me in Newcraighall now.” Four days later My Childhood won the Silver Lion. I should have been able to add that his career took off. But we were living in Britain. Over the next nineteen years, one of the few authentic voices of British cinema made only three more films.

Bill’s Trilogy was, in fact, the result of a sleight of hand. When I took over from Bruce Beresford as head of production for the BFI in the summer of 1971, he had left me two piles of scripts on the desk: one, very tall, of rejects and one, very small, of possibles. On top of that pile was a script by Bill Douglas entitled Jamie. I had never read anything like it. No standard ‘slug’ line for each scene — ext/int. location, day/night — spare description of setting, no emotional padding. Instead, the ‘facts’ of the shot were implicit. There was no depiction of an event which would somehow be filmed, but a series of images and sounds which, simply and concisely, communicated feeling. It was visual storytelling. It was cinema.

We gave him most of the money in the kitty, £3,500, which included the maximum personal grant of £150. At the very first rushes, he announced himself. His commitment in the scripting had carried over into the shooting.

There was no coverage of scenes from different angles; uncompromising, he went for the unique shot. And each shot had an intense clarity of line and feeling. He was a poet.

I realised that the industry was not ready to back Bill. The BFI presented a different problem. At that time the BFI Action Committee was pressing the governors to support collective film-making. The committee was opposed to feature films and would have raged against anything so undemocratic as giving two grants to one film-maker. One ‘solution’ put forward captures the spirit perfectly: that the applicants should spend half a day discussing the ‘economic, social, political and aesthetic’ consequences of their work.

I was wondering how to back Bill’s next film in such a destructive climate when the answer came in a roundabout way. Bill, encouraged by Lindsay Anderson to admit the nature of his film, changed the title to My Childhood. I jumped at this. With the echo of the two great childhood trilogies of Ray and Gorki, I felt I could sell the board the idea that we had not supported a whole film, but only part of a film — the first part of a trilogy — and that we were already half-committed to the other two parts. The chairman, Sir Michael Balcon, and Stanley Reed, then director of the BFI, supported the wheeze. And so the Trilogy was born.

Directors of films are like conductors. One way or another, they have to get the orchestra to play their way. Toscanini did it through terror, Bruno Walter through benign persuasion, Bill through communicating pain. During the writing he described the shot as it played in his head; during the shooting he did not have to find it, he had to re-create it. It was, he would say, and he believed it, ‘Simple Simon’. However, it didn’t leave much room for collaboration. Later, when he taught at the National Film and Television School, he put it succinctly: to ignore a bad suggestion is easy; to ignore a good suggestion that is irrelevant is what makes a director. If he didn’t get the shot he wanted, both he and the unit paid for it. He would literally go mad. It was never a performance; he was not a prima donna. He didn’t care much for status or money — it was the work. Still, I wanted to kill him sometimes. I was determined that nobody should do it but me.

Even now my children remember being woken at unearthly hours with calls from the Bill Douglas front. At 2 a.m. after the first day’s shooting on My Ain Folk, Peter Harvey, the sound engineer, rang me from Scotland. “Bill’s breaking up — we need a psychiatrist. He only did one set-up today. The crew want to go home.” I promised to join them the following day. When I arrived in Newcraighall everything seemed absolutely normal. Bill was cheerful, the crew co-operative, but although it was past 10 a.m. I noticed that the slate showed Scene 2, Take 3. I cancelled the shooting for the day. Bill quickly agreed. The crew were all keen to tell me what had happened, but I wanted to hear it from Bill.

For the rest of that day Bill was at his most charming and relaxed. I was beginning to wonder whether he would ever get to the point. I needn’t have worried. The next morning Bill joined us at breakfast looking ashen grey: he was cooked and ready. He sat down and pointed at Peter Harvey. “I want Mr Harvey to pay for my typewriter.” He suddenly sounded very Scottish. “He made me throw it at the bedroom wall.” The crew started to find their cereal bowls extremely interesting. “How did he do that?” I asked. “He ruined my shot.” Bill explained that on the first scene — where the officers fight violently with the boys to try to take them to the Home — the sound tape had got twisted on the final and ‘perfect’ take. Ludicrously rational, I said, “That’s your responsibility, Bill. If you’d killed someone, would Peter go to jail?” “He’s ruining my film!” He waved wildly. “I won’t work with them.” “That’s the best crew I can find. If they’re not good enough, cancel the film. I’ll ring the chairman.”

Even now I don’t know whether I was bluffing. I made for the public telephone in the alcove. As I started to dial, I heard a thundering of feet. Bill was rushing towards me, the crew following behind. He took the phone from my hand and tied the cable round his neck. “You’re ruining my life,” he cried. “Don’t. Don’t do it.” Stupidly, I found myself saying, “Pull yourself together, Bill.” Eight hard days later I left Edinburgh. As the plane took off, I breathed oxygen.

Bill’s style matured on My Ain Folk. He used to say: “Never show the audience something they can imagine better than you can show it.” It’s a motto that should be on the entrance to every film and television studio. His style consisted in creating gaps between scenes — scenes which were often single shots — which the audience would mentally have to jump across. It made them run: it was exhilarating. In My Childhood, for instance, the scene of Tommy beating up Jamie cuts to the boys and the grandmother sitting in front of the fire and then Tommy puts his arm affectionately round Jamie’s shoulder. Sometimes he went too far and created a gap which the audience couldn’t or didn’t want to cross. But at his best, as in this section from My Ain Folk, he touched the sublime:

“The frightened boy runs out of the house followed closely by a mad Mrs Knox, knife in hand. But she doesn’t pursue Jamie. Instead she makes for the house immediately next door. She bangs her fist on the door.

“Mrs Knox: ‘Ya whore, ya whore, ya whore. Bitch! Bitch! Bitch! Bitch out of hell!’

“Jamie running away. Disappears over the brow of a hill.

“Jamie, his hand held by a policeman, returns to Mrs Knox’s house. The policeman knocks on the door.

“Classroom. A rear view of children behind desks. They are singing. Jamie is finally isolated. ‘Summer suns are glowing / Over land and sea / Happy light is flowing / Bountiful and free / Everything rejoices / In the mellow rain / Earth’s one thousand voices / Join the sweet refrain.’

“Jamie has wet the floor. All the children front view. ‘All good gifts around us / Are sent from heaven above / So thank the Lord / Oh thank the Lord / For all his love.’

“And as the singing continues we see what will become of the children.

“We are in the cage, inside the pit shaft gate. Once more we are leaving behind the good light and once more the black earth is rushing up to shut it out.

“Miners’ faces in the darkness of the cage. Blackness. Pinpoints of light from the miners’ headlamps bob up and down and reflections of the lights break up in the dark water.”

Bill gave the script to very few people. He felt that everyone who read it became a kind of director, pulling in a different direction. Actors were given their scenes on the day. His reasons were broadly Bressonian, but also, as he used a mixture of professionals and non-actors, this approach put them on an equal footing, resulting in a consistent style. I felt that secretly actors liked his way of working. Particularly as there were hardly any lines to learn on the day.

I was present when Helena Gloag, who played Mrs Knox, confronted Bill. “Paul [Kermack, who played her son] tells me that in the film he has an affair with the lady next door. Why didn’t you tell me, when I did that scene outside?” Bill was unmoved. “How would it have helped you?” She considered this for a while and admitted, “It wouldn’t have.”

I left the BFI and went abroad, the funding of My Way Home secured. When I returned Bill had finished the Trilogy and was a world name. At home, he did not receive a single offer. I gave him a job in my department at the National Film and Television School, teaching screen-writing and directing. This essentially shy and private man turned out to be an inspired, and much loved, teacher. His influence can be seen today in the work of many film-makers.

Another impact is less known. I had persuaded Stanley Reed, Michael Balcon and the chairman of the BFI, Denis Forman, to concentrate on feature film production. Denis secured government finance by pointing to Bill’s success and to the fact that a film costing only a few thousand could command such respect.

In 1977, Bill and I talked about his adapting the Scottish classic, Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Bergman and Mackendrick, among others, had tried and failed to crack it. It was not until 1979, when I was managing director of the National Film Finance Corporation, that I was in a position to help. Before I was able to commission him, a friend sent me a treatment of Justified Sinner written by a young writer. Perhaps lacking the necessary ruthlessness, Bill and I agreed to give him time to try his luck and, instead, the NFFC commissioned Bill to write Comrades. It was on the NFFC pending list for more than four years before Jeremy Isaacs and Channel 4 put up the balance to make it.

What one needs most in British cinema, apart from a ten cent cigar, is three lifetimes. Eleven years late, I commissioned Bill to write Justified Sinner. I am not alone in thinking that it is Bill’s best script. In their wisdom, all the British sources of finance have passed on it. But they did give me advice. Lots of it.

Sadly, the frustration and disappointment over Justified Sinner strained our friendship. I hope that when the film is made — and it will be — I can, in my mind at least, make peace with him.

Bill lived the kind of life that some comfortably-off people feel artists deserve. He never made any money, and life was tough. God knows what it would have been like without the support of his companion, Peter Jewel. But he had his vision. Even when he was at his most impossible, a part of me stood aside and cheered him on: to set aside the reasonable and the possible, to reject compromise, to fight for that vision.

Originally published in Sight and Sound, November 1991

1 thought on “Bill Douglas – His ain man”

Comments are closed.