A brand new forty year-old British film, Franco Rosso’s Babylon, has been released in the USA to startling reviews. The film’s subject is black youths in south London, fun and fight jostle – its theme racism, its attitude defiant, its voice Reggae. The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1980, and received very good notices back home. It played well, but some exhibitors feared its reception might be too exuberant – and demurred. The film’s importance was underlined when Lord Scarman, who led an inquiry into the Brixton Riots of 1981 which took place in the very streets seen in the film, asked specifically to see Babylon. Its authenticity and veracity made it a historical document. It was initially invited to the 1980 New York Film Festival but then was quickly banned for fear it would exacerbate racial tension. A very good film is always new, but what adds relevance to Babylon in 2019 is the furore around Green Book and BlacKkKlansman. The embers of resentment have been rekindled about who owns the stories of black life.

The history of the making of Babylon may add another dimension. It was mainly financed by public money, by the UK’s National Film Finance Corporation (NFFC). In January 1979, I had just been appointed managing director. At my first Board meeting I proposed funding Babylon; my chairman, banker Geoffrey Williams, later said that Babylon was a multiple risk: a difficult and unfamiliar subject, a first-time director and a commitment of over eighty per cent of the budget as against the accustomed thirty per cent. I had no reservations.

The NFFC was formed in 1950 and part-financed 500 features in its first ten years. By the late 1970s the corporation was hard hit by cuts, and the stream of films were reduced to a trickle of two or three features a year. Every decision became significant, every game a Cup Final. Worse was to come. Within months of my joining, the Labour government was ousted and the Tories took over. The incoming Tory films minister, Norman Tebbit, (now The Lord Tebbit CH PC) decided that £1.5m per annum, funded via a box office tax, should suffice – £1.5m a year for a population of 60m, that is 2.5p per person. What mattered to all governments was television. My friend and teacher, the film and theatre director Lindsay Anderson, used to say that, on cinema, the English were philistines. My chairman, Geoffrey Williams, while at a prestigious public (English patois for ‘private’) school, was discouraged from visiting the local cinema because that was ‘where one picked up communicable diseases’. Geoffrey, an inveterate cinemagoer, ignored the ruling and looked in rude health to me.

The writers of Babylon, Martin Stellman and Franco Rosso, did not originally have a director or a producer attached to the project. Martin was a former student at the National Film School, where I had been Head of Directing. I knew something of the script’s history – that it had been developed by the BBC, who had passed on it, as had the British Film Institute Production Board under Peter Sainsbury, where I had been head of production previously and, ironically, where the last film the Board had backed just before I left, was Pressure (1976) the first British black feature, written and directed by Horace Ove. The central figure of Pressure is a first-generation young black Brit, who does not fully belong in either the black or the white community. This is not the war zone of Babylon but a place where racism hides behind the everyday and is expressed through exclusion or diminution in all the areas that create communality and community: housing, education and jobs. Ironically – and optimistically – it is a white teenage girl who expresses her outrage of white racism. But there is police violence, possibly rogue: ‘The law is not concerned with you and your lot,’ says a plain-clothes officer during a brutal police raid of a legitimate political gathering. Horace Ove said afterwards that his next film would not be a black film but a film.

Ghettos come in all colours, shapes and sizes. The Board also backed the first feature about the Asian community, A Private Enterprise (1975), directed by Peter K Smith and co-written with Dilip Hiro. Set in the Midlands, it was neorealist in style and remarkable in its breadth, touching on the lives of a young entrepreneur who wants to fit in, strikers at a white-owned factory, a conservative older generation, nouveaux riches whose lives centre on shopping in Harrods, and semi-detached white liberals.

I never backed a film solely because of its ethnicity; it is others who did not back a film because of its ethnicity.

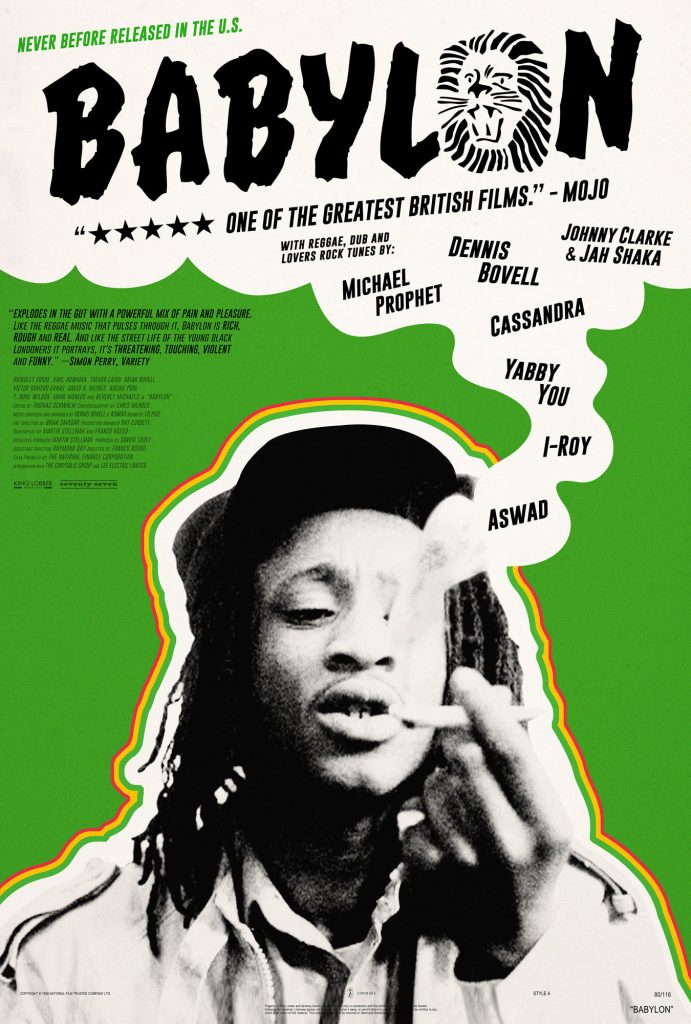

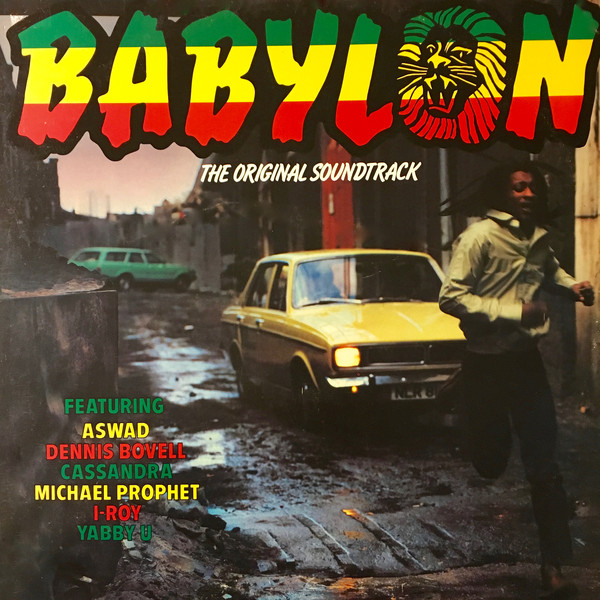

Franco and Martin were inclined to ask Stephen Frears to direct. I admired Stephen’s work, but I thought he would be a foreign correspondent. I proposed that either Franco or Martin should direct. It became Franco’s first feature. Franco and Martin knew the subject intimately. Franco, a documentary editor, was born in Turin, came to Britain when he was eight and lived in South London, where Babylon takes place. In fact, young black men played Reggae and their sound systems at the bottom of his garden and annoyingly kept his children awake at two and three in the morning. Martin, the son of Jewish immigrants, was screenwriter on Franc Roddam’s Quadrophenia (1979), and had worked as a youth and community worker in the area. Chris Menges (later Oscar winner for The Killing Fields and The Mission, and who had, memorably, shot Ken Loach’s Kes,) joined as cinematographer and Gavrik Losey, son of Joseph Losey, as producer. Through determination and ingenuity, Gavrik found the balance of the budget. The composer was the legendary Dennis Bovell, the lead Brinsley Forde, actor and founder of the Reggae band Aswad, and all the main actors, bar one, came from the black community. They did not act; they embodied their roles. Italian neo-Realism was a conscious reference for Franco – and the cast had escaped conventional training. The film was unusually physical for the time and for an English film.

The days of white western hauteur, sense of superiority and entitlement to speak with authority about and on behalf of just about everybody else are coming to an end. But the situation is not clear-cut.

There was controversy in the sixties when the Free Cinema middle-class directors (Tony Richardson, Karel Reisz, Lindsay Anderson) made films about working-class subjects: A Taste of Honey, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, This Sporting Life and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. The screenwriters, however, were all working-class, at the top of their game: Shelagh Delaney, Alan Sillitoe and David Storey. Collaboration was key.

Or take Algerian public investment in The Battle of Algiers (1966). This account of epic struggle and the creation of a nation was directed by Gillo Pontecorvo and co-written with Franco Solinas, both Italians. India, too, backed an outsider to tell the story of one of its founders: Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi, was part funded by the Indian Film Development Corporation. Also, significantly, Jack Lang, France’s minister of culture, approved Andrzej Wajda, the great Polish director, to direct Danton, a historical figure and the voice of the French Revolution.

Creatively, the line should not be drawn between the outsider’s or the insider’s view – the line should be blurred or even fractured so as to surprise and illuminate. The watchword is authenticity – difficult to define but easier to recognise.

After Tebbit became our boss at the NFFC, we sat on our hands while we waited for him to decide what to do with us. When government, any government, announces a review, the outcome is either ‘deep-sea diving boots’ or ‘the blindfolds’. In the interim, Tebbit appointed two new members to the Board. I was curious as to how he would react to the NFFC’s exceptional support of Babylon, which had been backed when Labour was in office a few months earlier. I did not have to wait long. I was summoned to meet a panjandrum, Sir Leo Pliatzky, from the elite of the civil service to learn our fate. We met in his office in a Georgian terrace house. The room had a high ceiling, tall doors, long windows and pale green wallpaper. It was more an eighteenth century salon than an office. He was courteous, offered me coffee and asked a few questions. Then he got down to business. It was to be the ‘diving boots’, to slow us down. Our budget would be cut. (I did wonder whether they wanted us to fail so that they could close the shop. If that was the aim, we were not cooperative – an NFFC-backed film participated at the Cannes Festival every year I was there and the Corporation put up 60% of the budget of £200,000 for Gregory’ Girl, which, it is reported, has grossed £25 million.) As I put my hand on the door handle to leave, he piped up behind me: ‘Mr Hassan, I take it you are going to back radical films and the like.’

Maybe he was thinking of Babylon. Or the films I had backed at the BFI.

‘Shouldn’t I?’ I asked.

‘Did I say you shouldn’t?’ he said.

‘No, you didn’t. I’ll remember that,’ I said.

I went back to my office and prepared for a siege. The next two films were David Gladwell’s adaptation of Doris Lessing’s novel Memoirs of a Survivor, scripted by Kerry Crabbe, and Bill Forsyth’s Gregory’s Girl. I did not see Babylon as a stand-alone film. Together, all three films were about young people in a changing world: hostile in one, shattered in another, and the last apparently normal but actually heralding a new era.. ‘Gregory’s girl’ might be Dorothy the girl footballer, Gregory’s ideal, but two others also make a claim Gregory’s young sister, Madeline, and Susan, the girl who (quite literally) brings him down to earth. The three girls are the dynamic centre. Artists see today but also see tomorrow coming.

The National Film Finance Corporation was closed down in 1985, to be replaced, sequentially, by British Screen, The Films Council and The British Film Institute…

Copyright©Mamoun Hassan, June 2019