In August of 1971 Kevin Brownlow returned from the Moscow Film Festival, where he had shown Winstanley, with a tantalising prospect: Kurosawa was going to pay a rare visit to London on his way back to Tokyo. I thought I would try to arrange a reception. Unfortunately, Stanley Reed, director of the BFI, was in hospital recovering from a heart attack and the deputy director, and legendary head of the national Archive, Ernest Lindgren, did not rate Kurosawa. With some trepidation I phoned Stanley in hospital. A little while later, Ernest rang to tell me tersely that he would agree to a reception—on condition that it did not cost too much. And so it was that Kurosawa had a meal in the BFI canteen with, among others, Lindsay Anderson, Stanley Donen, John Schlesinger and Kevin Brownlow. Scores of filmgoers in the BFI canteen watched disbelievingly. It was the perfect venue.

Kurosawa was in one corner of the hospitality room with some Japanese companions. He was standing with Madam Kawakita, dressed fine in a kimono, who was a legendary figure on the festival circuit, and wife of Nagamassa Kawakita, owner of Toho studios and two companions. Lindsay was ten feet away chatting with Stanley Donen, Barbara Aptekman. I joined them but my attention was entirely on Kurosawa, and I was wondering what the hell to say to him. Kevin appeared from nowhere. He had interviewed Chaplin and Buster Keaton the greats of the silent era ‘What are you doing wasting your time talking to Stanley Donen’ he asked impatiently. Stanley retorted, ‘Kevin!’ Kevin knew I must not waste this chance. He clutched my arm and dragged me by the arm and left me standing in front of Kurosawa’. That was the beginning of one of the most extraordinary and fulfilling conversations I have ever had.

Akira Kurosawa was a proud man, nicknamed Tenno or the emperor, but he disliked court culture, pomp, celebrity, show biz and most critics. Distaste for these peripheries would diminish with the lessening of his powers, but that was still in the future. On that evening I queued with amazed and delighted filmgoers to get him some food, but he ate hardly anything. However, he did drink. He put a hand on the whiskey bottle in front of him whenever anyone tried to move it. He was not your stereotype inscrutable Japanese—he was six foot three, informal, urbane, and relaxed. As he was leaving, he playfully locked the much shorter Anderson in a judo hold.

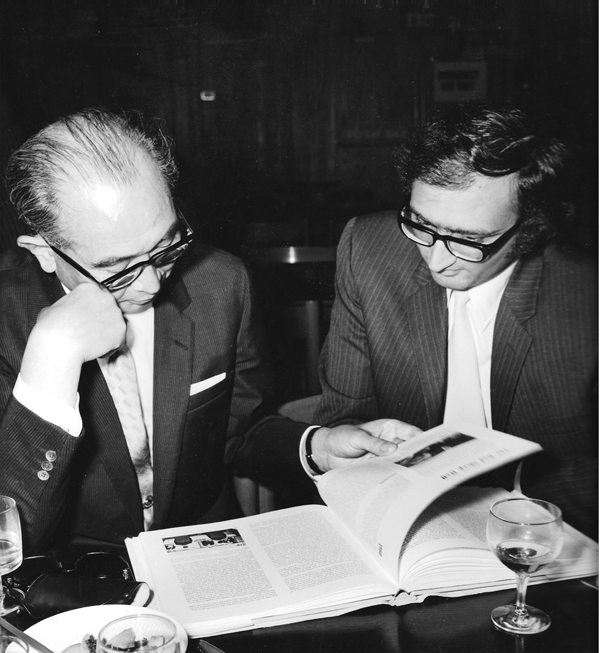

I sat next to Kurosawa all evening; I was sitting with Homer. He absolutely refused to discuss the meaning of his films: ‘You either like my work, in which case there is no point in talking about it, or you don’t like my work, in which there is no point in talking about it.’ But the making of his films was something else. He lived the telling of it. I carried Donald Richie’s magnificent The Films of Akira Kurosawa, hoping to get an autograph. Kurosawa and I leafed through it and he’d make the odd comment and on occasion he reacted surprised as if he’d not seen it before. He was particularly excited about his use of multiple cameras and drew on a paper serviette the movement of four cameras on the set of The Lower Depths. I still have that serviette with a trace that might have been left by a spider that had accidentally fallen in an inkpot. Though he was by then some way through the whiskey bottle. (However, looking at it later, it made clear sense.)

Lindsay Anderson made a brief speech, slamming the BFI (he had said that it was the ‘duty of the artist to bite the hand that feeds him’), and paid warm tribute to Kurosawa. Madame Kawakita, who spoke excellent English, translated his response: ‘He cannot speak except in film. Let us drink.’

As it turned out, 1971 was a particularly significant year. There was a before and an after. The innovation, the great films, the time when Kurosawa could command – all that was before. And after? Kurosawa asked me how old I was. I said thirty-four. He spoke and I interrupted before Madam Kawakita finished translating. ‘I know,’ I said. ‘Mr Kurosawa was thirty-four when he directed his first film, Sanshiro Sugata.’ He gave me a big hug. I looked over his shoulder at Madam Kawakita’s face. I found it hard to keep back the tears. She translated Kurosawa’s next words. ‘There are only good days ahead.’

Early the following year, Kurosawa tried to commit suicide. Maybe the future promised only long, unbearable periods of dumbness and silence. Lindsay and I agreed that to congratulate him on surviving the attempt might be tactless. We cabled, wishing him ‘the best that he wished himself’. We knew what that was. However, he was to make only six more films. One in the Soviet Union, two with American money, one with a French producer, and two Japanese-funded. Like many of his generation, Kurosawa was, for all the problems, at home in the studio system. Outside it, he was in a kind of exile. Hustling did not come naturally; and, although he was often criticised for being too western, aiming at a world, rather than a Japanese, audience blurred his focus.

I next met him fifteen years and three films (Dersu Uzala, Kagemusha and Ran) later at a reception held for him by the BFI at the Dorchester hotel. This time no expense was spared; it was a banquet fit for an emperor. Everybody was there. I shuffled along to shake his hand; I sensed that something had gone. He was older, of course, but the energy was diminished. I asked him if he recalled the previous meeting. He nodded, then spoke in a tone that sounded – no, felt – defensive. He did not want to be reminded. His translator was a striking young Japanese woman in a little black number, who spoke with an American accent. Everything had changed, he said. These days he spent his energies trying to get his films off the ground – and then trying to sell them. For a man who, in his heyday, had made his films and then stood aloof and prepared his next film, this must have been torture. Or maybe it was some compensation. Attending award ceremonies, listening to endless tributes and receiving honours may have punctured the silence. And he was, against the odds, still working. He could, with good reason, echo the words of Kambei, the leader of The Seven Samurai: ‘We have survived.’ But that was not the whole story. Kambei’s next words are: ‘We have lost again.’

(I looked at The Seven Samurai with students from the National Film & Television School for the C4 programme MOVIE MASTERCLASS in 1988. I sent Kurosawa the video. More of that later)

Copyright©Mamoun Hassan 2022

This article has been extended from the previous version from 2011, and is to be included in Mamoun’s forthcoming autobiography